Yasuyuki Nakai

Curator, The National Museum of Art, Osaka / Visiting Professor, Graduate School of Kyoto University of Arts

There are not very many methods for obtaining new images that are available to the creative person. One would be the principle of mimesis (imitation), which was the principle of expression for the ancient people, who depicted the phenomena before their eyes as they appeared. This was the core principle of expression for artists until the early 20th century when pure abstract art made an appearance. Another, as a polar opposite perspective, would be the method indicated by Leonardo da Vinci that through observing stains on a wall or combinations of stones, ‘anything and everything’ including scenery, conflict or the human body can be interpreted (1). Mina Katsuki’s method of expression through the brushstroke, does not necessarily portray specific phenomena as Leonardo exemplifies. However, like the compromising phrase of ‘anything and everything’ follows the exemplifications, if the object represented by the brushstrokes Katsuki expresses metaphorically presupposes the representation of a single world, it is possible to deem the expression as one that belongs to the latter methodology.

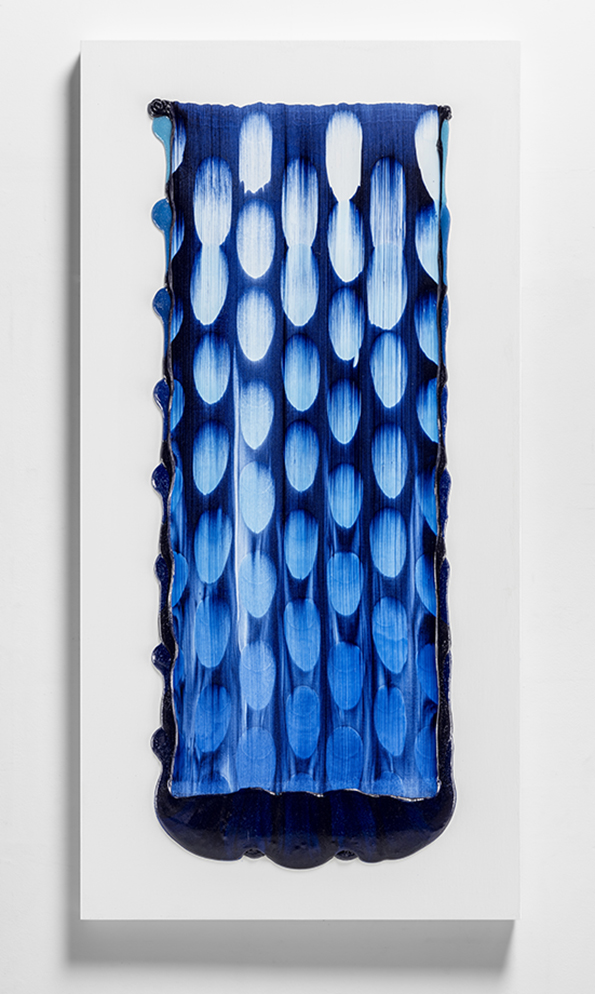

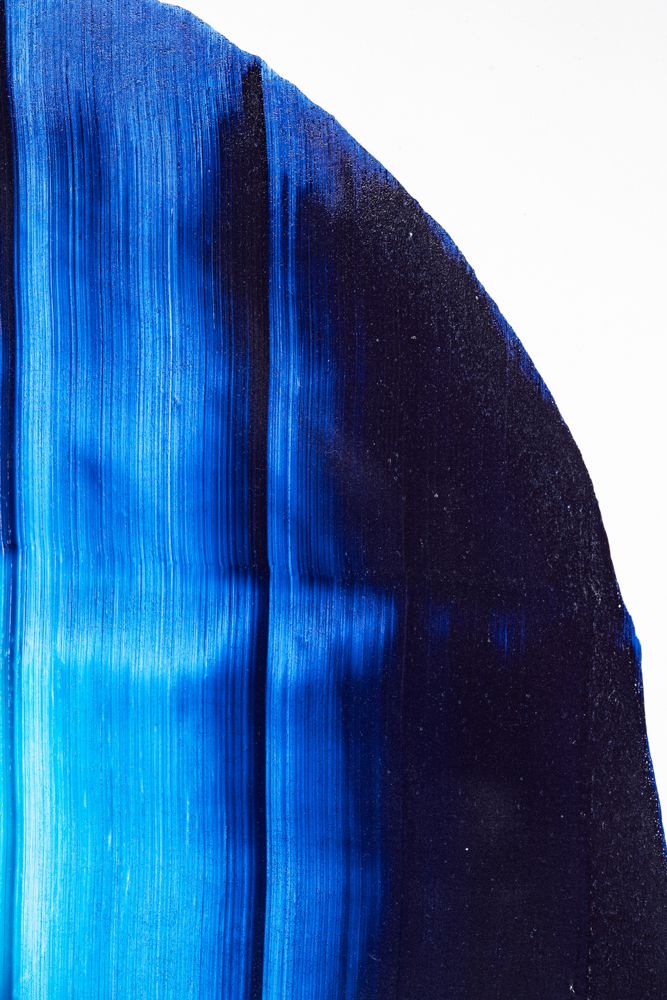

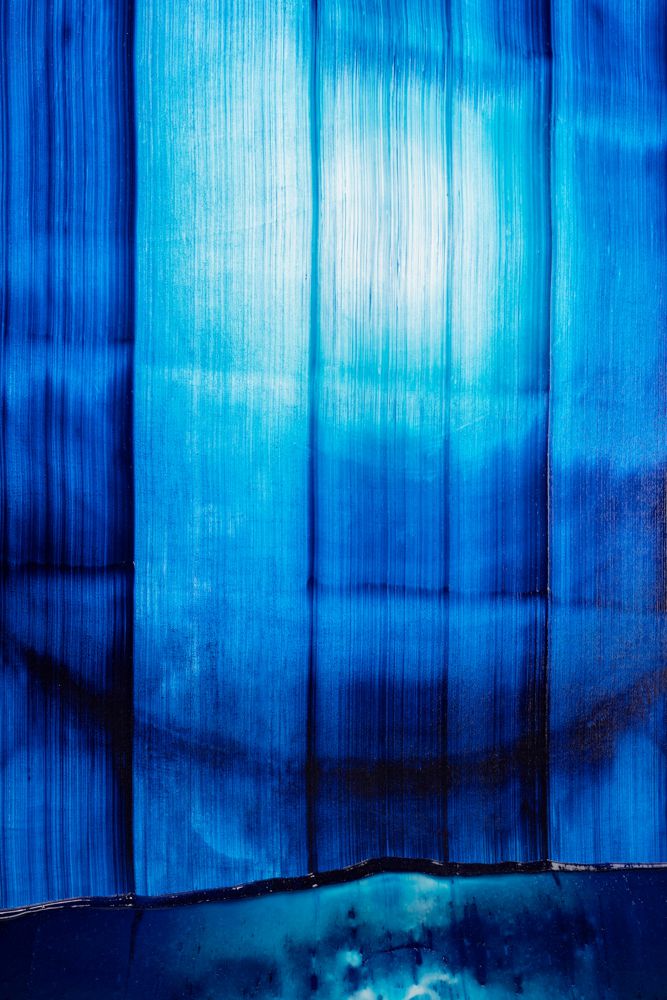

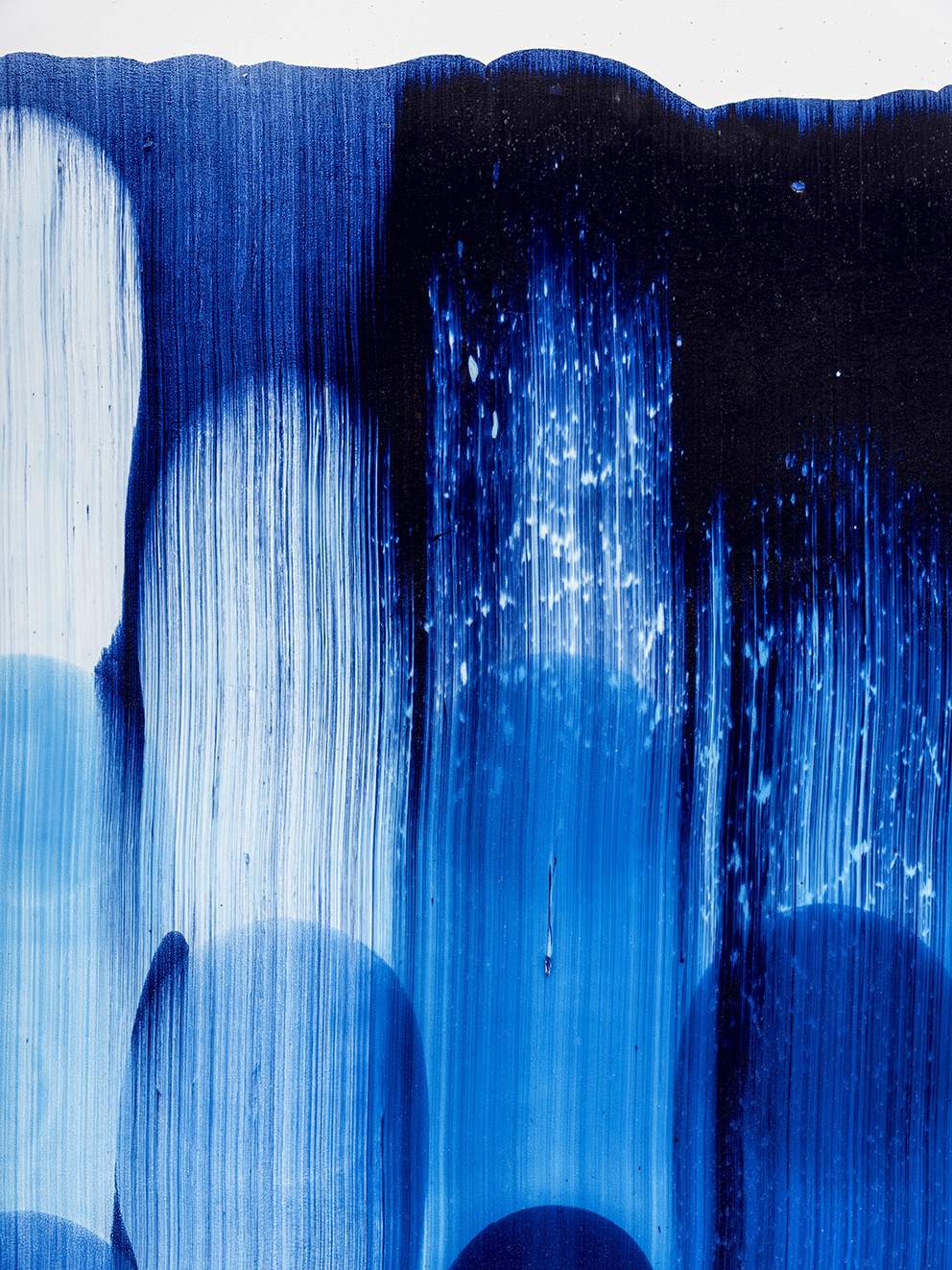

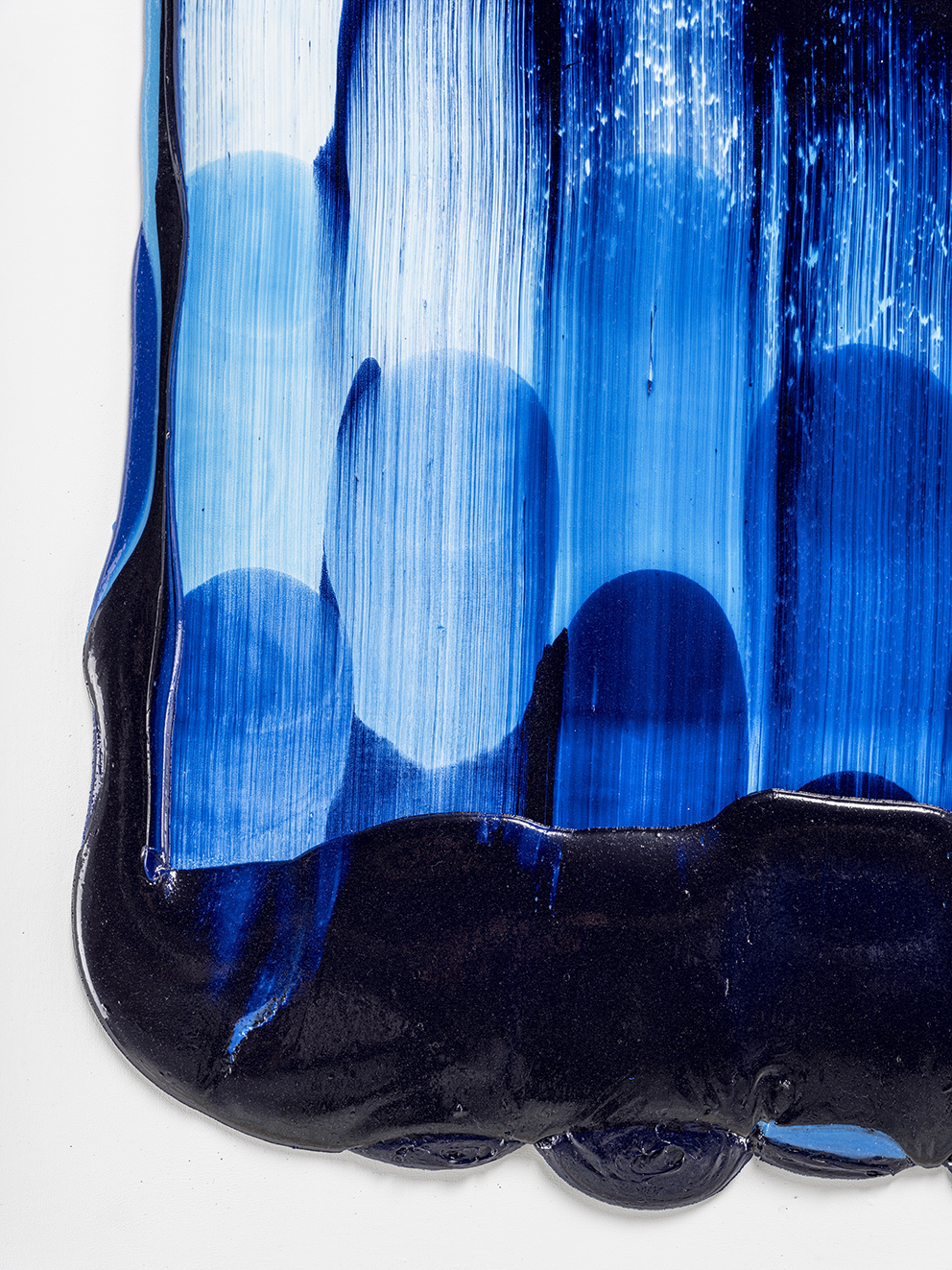

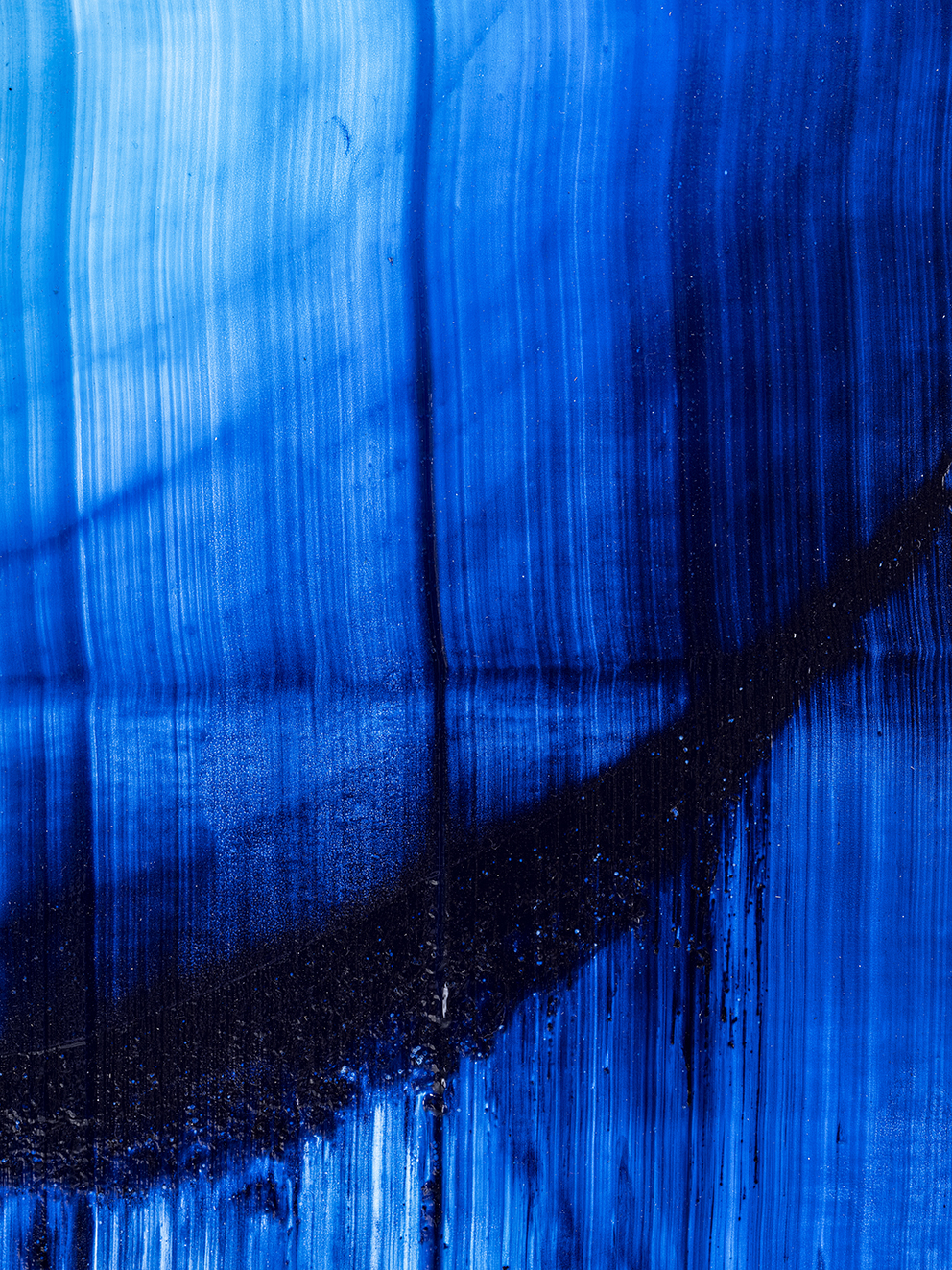

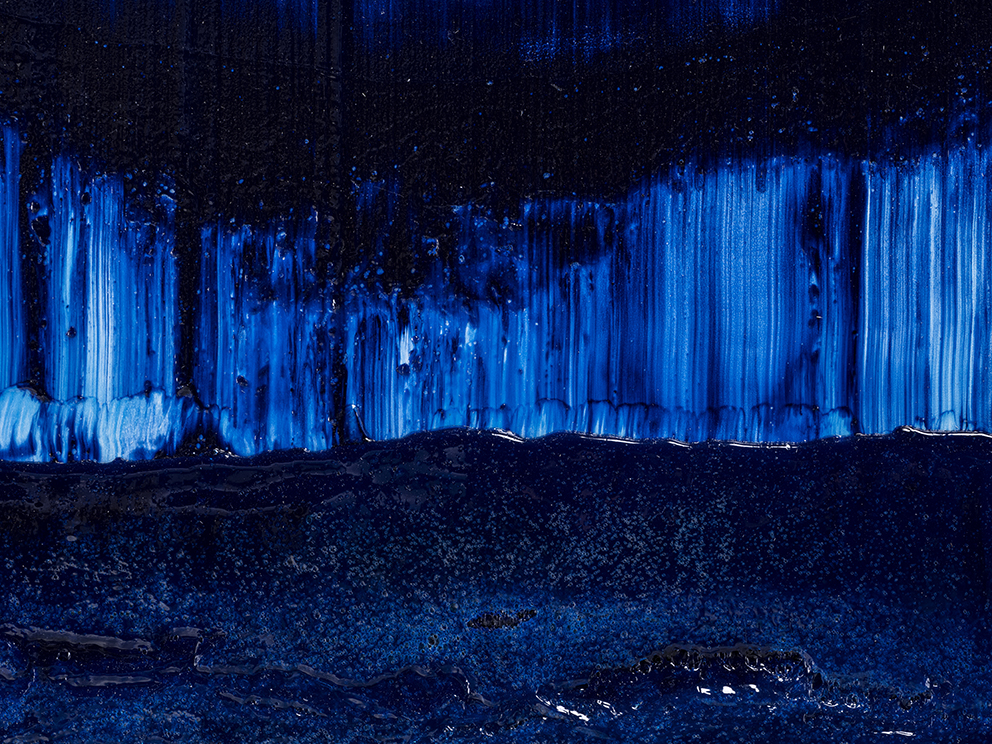

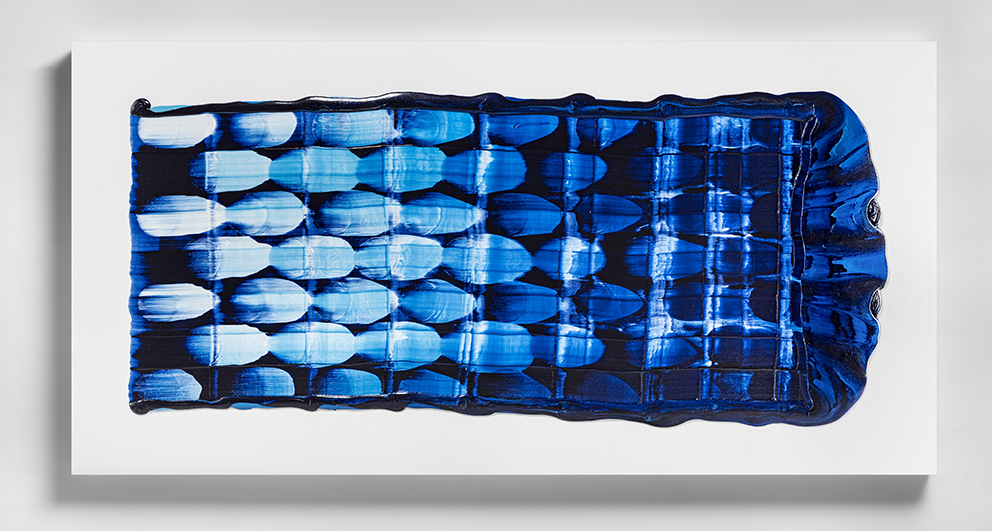

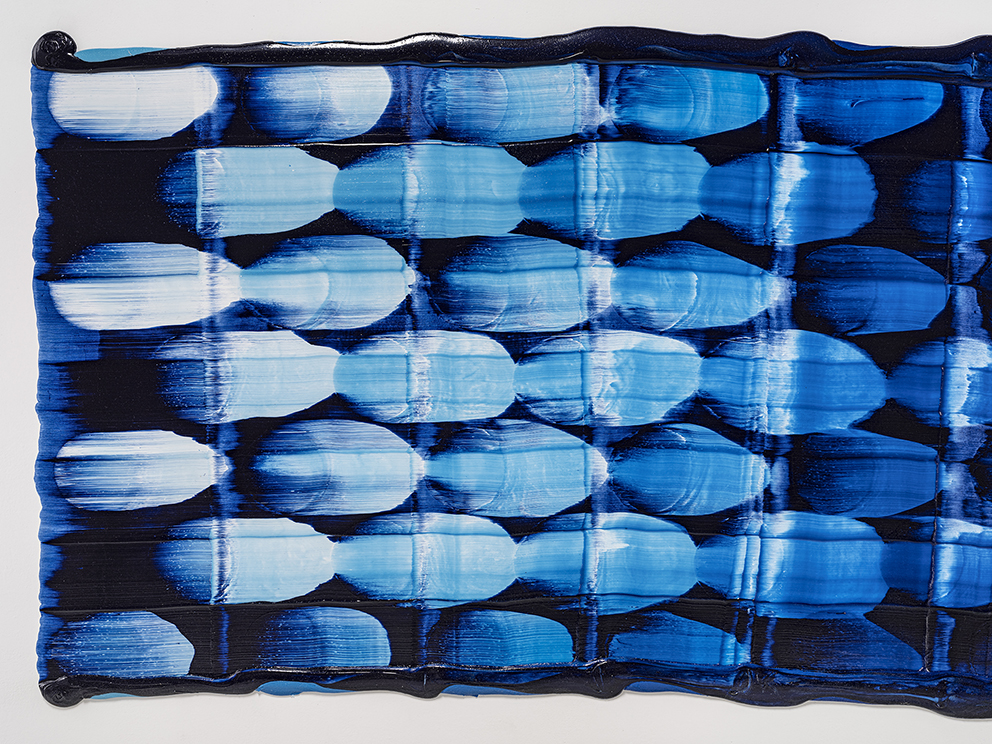

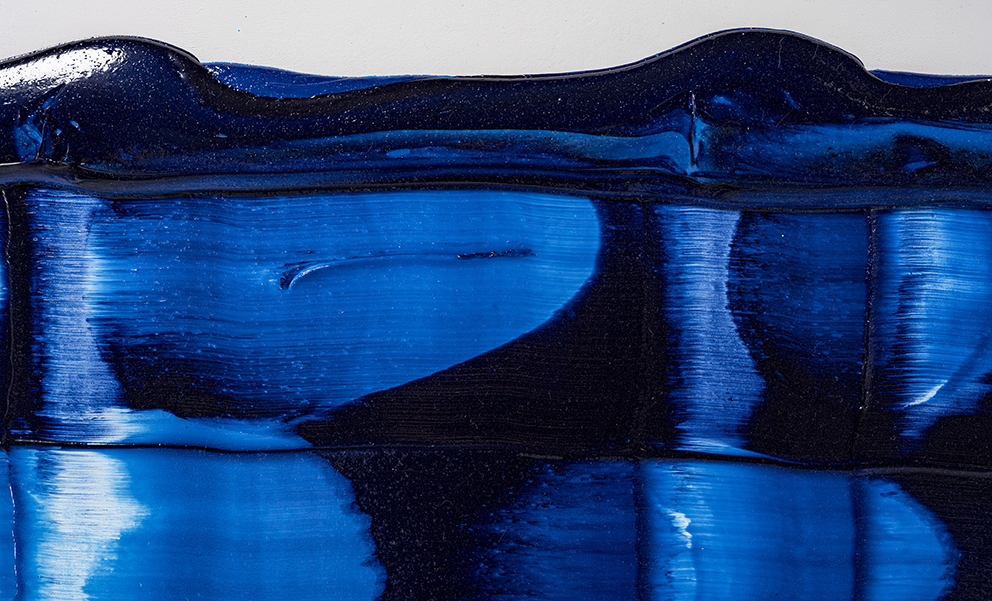

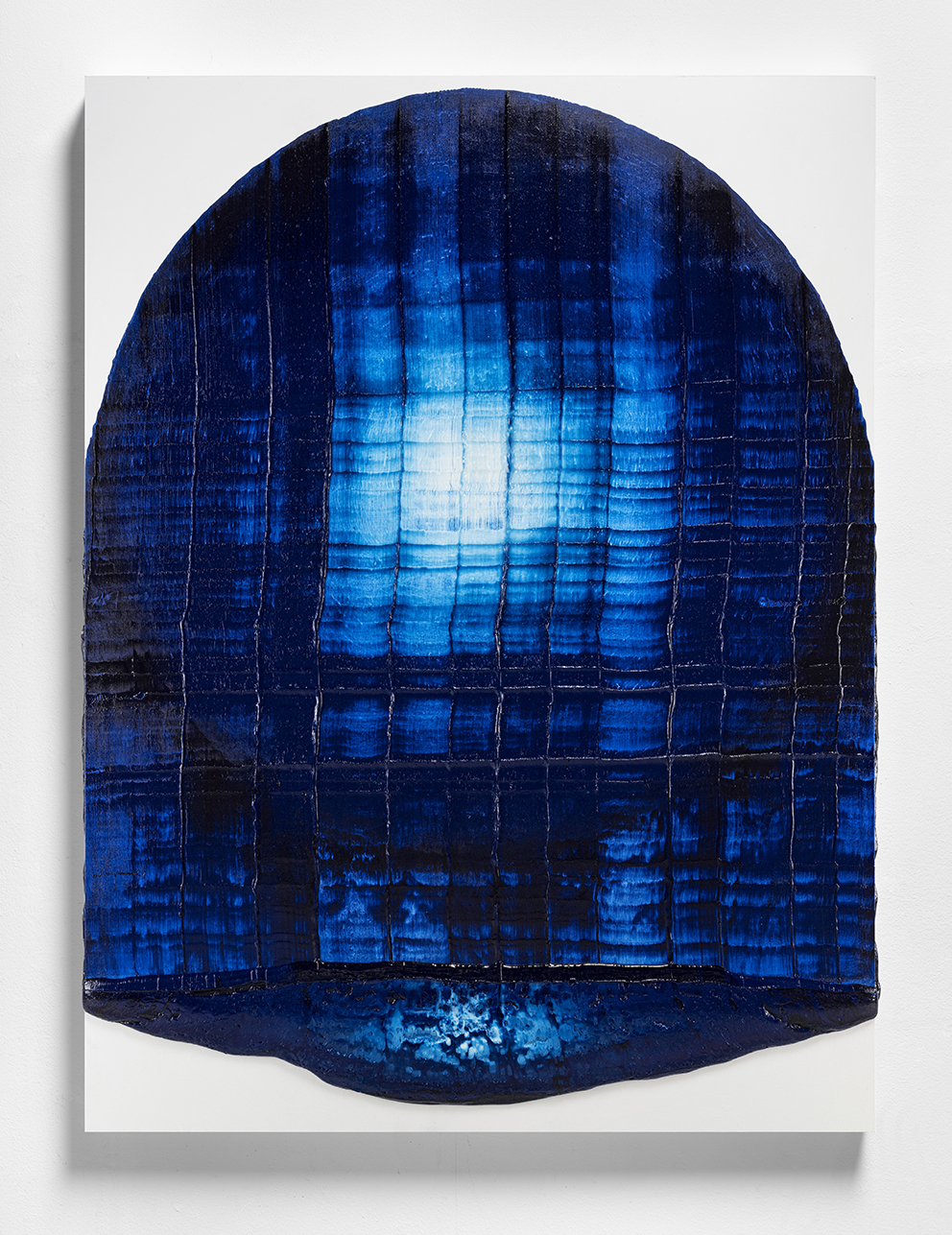

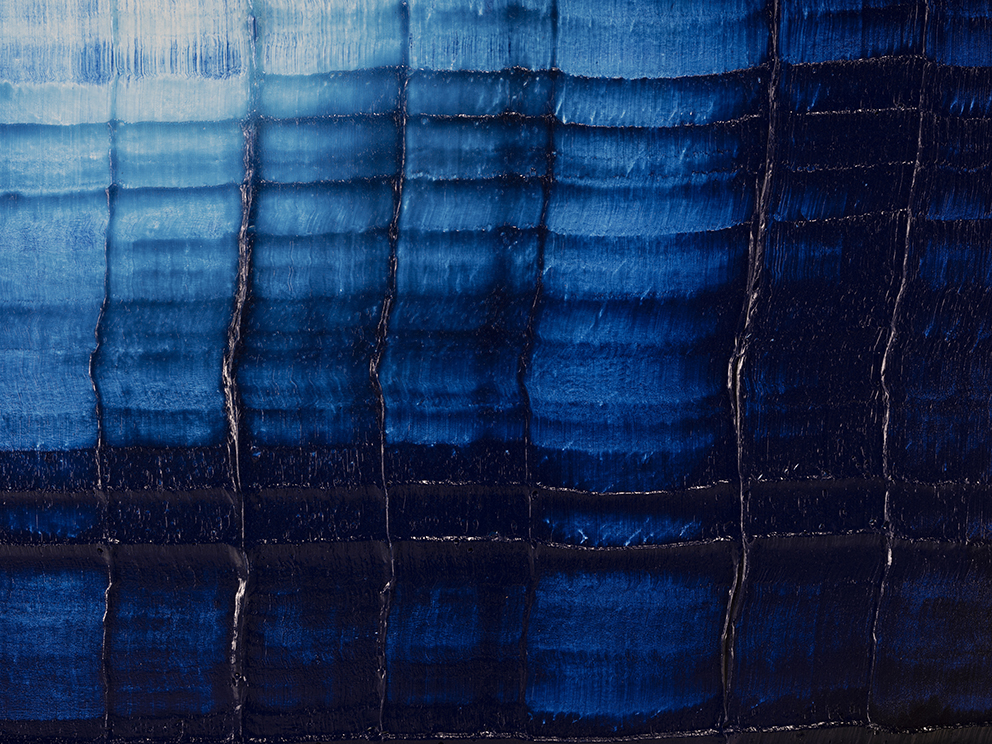

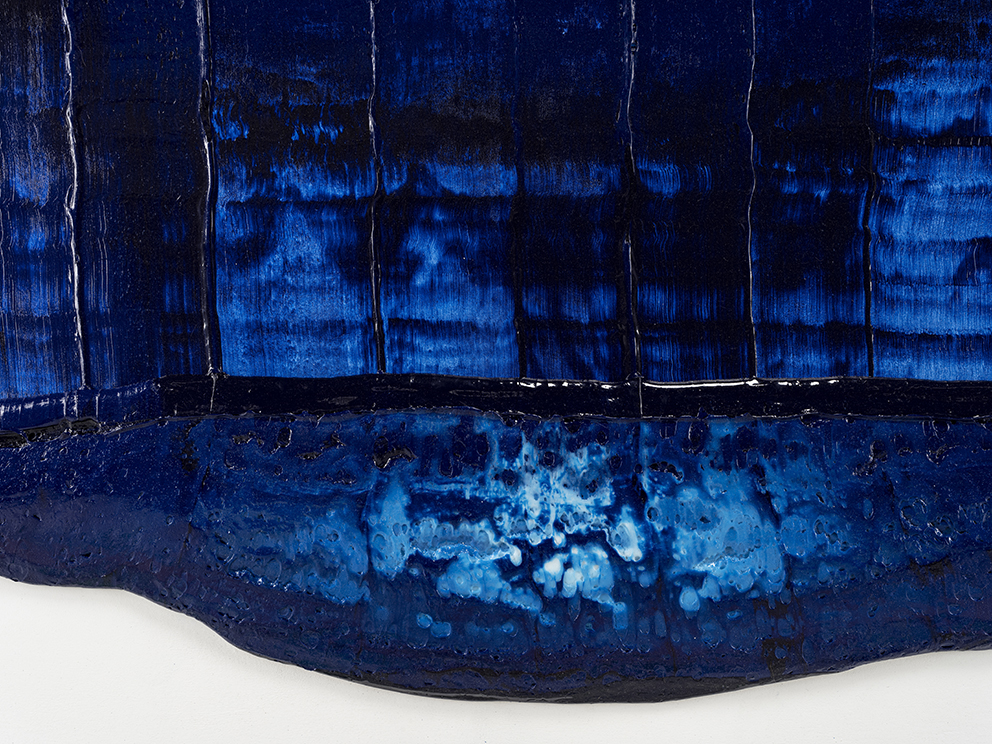

I may have jumped ahead too quickly; let us look more carefully at Katsuki’s expression. Her expression which may be characterised by the intonated brushstrokes utilising deep blue paint, is realised through a serial elaborate preparation. After creating a thick coloured plane of paints subtly varying in brightness from white to deep blue on the canvas, hypothesising the final icon, she then moves the mass of paints in one stroke from top to bottom leaving brush marks, using brushes installed in a row, to create the flowing brushstroke. This irreversible process creates an incidental pattern, which Katsuki even predicts that might turn out to be very different from the icon she imagines. As this sort of contingency is induced, unpredictable forms make their appearance, allowing the viewer and even the artist to interpret anything and everything.

This structure of creating the artwork in one go after extensive meticulous procedures, is reminiscent of Saburo Murakami’s paper-breaking performances. Though I said performance, Murakami himself seemed to understand this series of work as paintings. This can be presumed from the fact that the paper-breaking artwork presented at the First Gutai Exhibition, was exhibited along with his other pure paintings, with the broken pieces of paper after the paper-breaking was implemented at the opening ceremony. We can also see Murakami’s attitude towards this style of work in his preparation stage. Studying video documents of his paper-breaking work, we can learn that Murakami carefully finishes in gold, the front surface of the Kraft paper stretched on a large wooden frame - the device of the paper-breaking. Murakami also stretches the Kraft paper on both sides of the wooden frame, double-sided like the taiko drum, so that a characteristic sound is made then the paper is torn. This device is prepared as such, and with the opening of the exhibition, the paper-breaking takes place in front of the large audience of guests. The moment the paper is torn, the artwork is broken accompanied by a tremendous rupturing sound, manifesting this phenomenon, extraordinary for an art exhibition. Returning to my point, this structure in which such a dramatic visual effect instantaneously appears, seems to align with the system in which Katsuki’s artwork is created.

The huge flowing expression of the brushstroke which emerges in Katsuki’s artwork, through the processes previously mentioned, attaches a feeling of seeing a nostalgic scenery deep in our memories, though it does not resemble any images we are usually familiarised with. Without even a need to search for the origin of those memories, many of the Japanese will know of the history, that from old times Japan gave the name keshiki (lit: scenery) to forms which yielded abstract expressions. What exactly is keshiki? To borrow from Jiro Aoyama’s text on Japanese ceramics, it is “to grasp a single contingency”. (2) In fact, Aoyama’s statement was a word towards the Japanese tea ceremony, however, it is an analysis of tea ceremony made upon the presupposition that the ceramics which survived through Japanese history, are what created the avenue for tea ceremony. In other words, ‘contingency’ in Aoyama’s terms refers to historical ceramics, and one of the most important factors that determines the beauty of the contingency, is keshiki. I am certain that those who have read this far understand that by transcending masses of paint into expressions of the brushstroke in her work, Mina Katsuki devotes herself to trying to extract the beauty out of contingencies. In Aoyama’s words, this beauty may be something trivial that only belongs to the surrounding domain created through the world of Japanese tea ceremony. However, many Japanese artists place their lives on this trivial thing, and furthermore, by converting this expression into western painting materials, in a way, Katsuki hopes for its universality. Maybe if Aoyama hears of this practice, he may utter “crude” with a smirk. Either way, I still feel a sincere beauty inside Katsuki’s such attitude.

(1) ‘”Ancients” and Moderns” in art and science in Prague’ - The Mastery of Nature: Aspects of Art, Science, and Humanism in the Renaissance, Thomas DaCosta Kaufmann; translated by Eiichi Saito, published by Kousakusha (1995), p.255.

(2) ‘Ceramics of Japan - notes’ - Complete texts of Jiro Aoyama, vol.1, Jiro Aoyama; published by Chikuma Bunko (2003), p.126.